By Sadie Fleig, UC Berkeley undergraduate research intern

As the pandemic continues, farmers have struggled to maintain connections to a severely disrupted supply chain. With many restaurants and businesses having shut down or operating in limited capacity, farmers have incurred major losses. To help, the United States Department of Agriculture implemented two rounds of a Coronavirus Food Assistance Program (CFAP), as well as an additional food box program and emergency loan assistance. However, small-scale and BIPOC farmers often face major hurdles in applying for federal programs such as these. My research focused on assessing farmer relief programs for their level of accessibility to socially disadvantaged farmers.

Overall, federal funding programs fundamentally do not have structures in place to support small-scale farmers. The majority of federal programs deliver payments that align well with the standardized rates for large monoculture farms. In contrast, diversified and smaller-scale growers tend to finance themselves with a variety of local and direct-to-consumer channels. This allows them to receive income at a rate pertinent to their location and consumer base, which is not reflected in the USDA’s acreage or specialty crop percentage rates. In combination with farm subsidy loopholes, this discrepancy is demonstrated in the payment amounts for the first CFAP round, with $1.2 billion (20%) of the first $5.6 billion dollars in payments going to the top 1% of recipients, versus $1.5 million (0.26%) going to the bottom 10% (Rampgopal and Lehren, 2020). Furthermore, the top 10 percent of recipients received average payments of almost $95,000, while the bottom 10 percent averaged around $300.

In addition, federal relief program or loan applications are burdensome for most small scale farmers, as these forms are complex and come with few instructions or definition of terms, requiring extensive background knowledge. This creates a considerable barrier and a significant disadvantage for any farmers with English as a second language or farmers who have had minimal experience filling out government documentation.

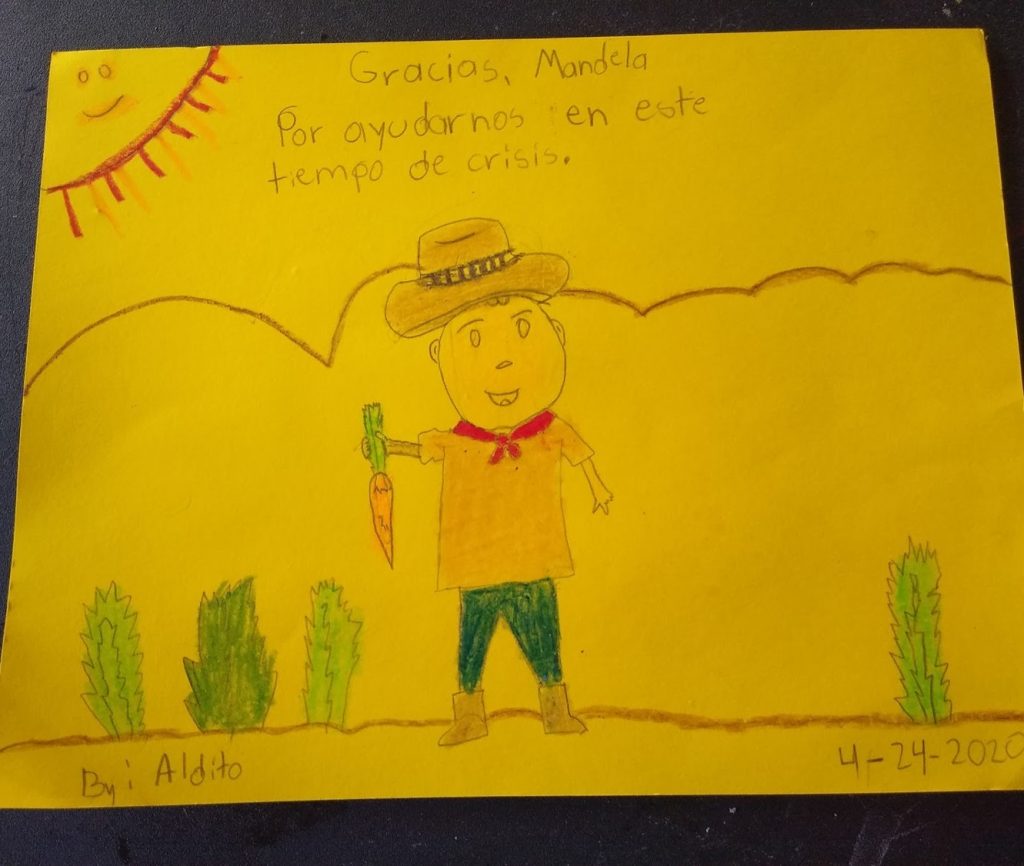

In spite of federal shortfalls, community based and non-profit organizations such as Community Alliance with Family Farmers and California FarmLink played an important role in mobilizing and administering community based and federal funds to support small-scale farmers during the pandemic. UC Cooperative extension provided vital technical assistance with CFAP applications for small-scale farmers with English as a second language. Organizations based in the community have a better understanding of the circumstances those farmers are undergoing and are important partners in relief efforts.

After careful review of the CFAP programs by the Biden administration, the USDA announced the “USDA Pandemic Assistance for Producers,” initiative to distribute resources more equitably. The current CFAP program will fall under this initiative. According to Vilsack, “Our new USDA Pandemic Assistance for Producers initiative will help get financial assistance to a broader set of producers, including to socially disadvantaged communities, small and medium sized producers, and farmers and producers of less traditional crops.”

In order to improve upon the discrepancies in programs for socially disadvantaged farmers, there should be an effort to amplify the support models that benefit BIPOC farmers and in the long term, advocate for those models to be utilized by the USDA. One general intersection point between determining local conditions and national funding are the local FSA offices that review their county’s CFAP applications, which is a good way to begin to implement services that cater more directly to BIPOC farmers. Although application forms are available in Spanish, it would be useful for FSA offices to offer forms in multiple languages, particularly those that are regionally prevalent. In terms of form simplification, the definitions sheet attached to the applications, should be expanded to aid growers in completion, and a general guide to the USDA loan documentation is needed. It is essential for federal agencies, particularly regarding agriculture, to begin to fulfill the critical needs of BIPOC farmers.